Soil Organic Matter: The Essential Guide

Written by

Kiana Okafor

Reviewed by

Prof. Samuel Fitzgerald, Ph.D.Soil organic matter is composed of decomposed biological materials, microbial biomass, and a stable form of organic matter known as humus.

Decompositional timeframes can range from just hours for sugars to millennia in the case of charcoal fragments.

Humus can hold 20x its own weight in water, thus helping significantly to reduce irrigation needs.

The primary stabilization for carbon storage in soil is through mineral-association and aggregate occlusion.

When properly managed, the application of compost and cover-cropping practices can increase SOM (soil organic matter) by 0.1-0.6% annually.

Regenerative soil stewardship increases agricultural productivity in addition to environmental carbon sequestration.

Article Navigation

Soil organic matter is the foundation of healthy soils worldwide. This consists of decayed plant roots, leaves, microorganisms, and animal residues, the transformation of which has occurred naturally. It can be conceived of as the natural recycling system that is constantly at work beneath your feet. It is quite different from the fresh surface debris or undecomposed material which may be seen in gardens.

Another essential reservoir stores more carbon than all forests and the atmosphere put together. Plants absorb carbon dioxide and secrete it underground through their roots and residues; this process is known as carbon sequestration. Each time the farmer or gardener makes a sustainable decision, it is building this reservoir with the rest of society. Your choices about the way you manage the land you tend influence global climate patterns.

Knowledge of soil organic matter will help you realize richer harvests and more resilient landscapes. This kind of study involves the complex composition of stable humus and microbial networks. Here, too, we shall explore practical methods of improving moisture retention and nutrient availability. These techniques will yield benefits for gardens and farms alike, large or small.

Managing this resource generates visible changes in growing seasons. I have seen barren fields made productive by compost systems. There are also visible alterations in the color of the soil, which tends to be darker and has a loose, crumbly texture when there is an adequate quantity of organic matter. These are independent, even better conditions for plant roots.

What Soil Organic Matter Is

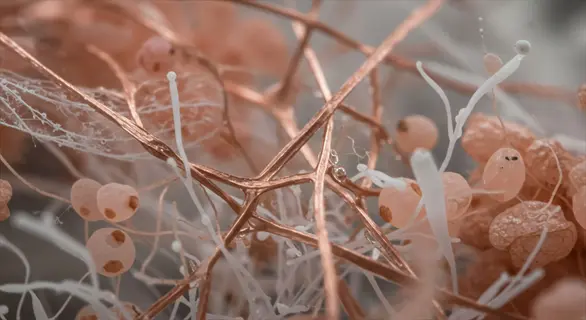

Soil organic matter consists of three rather separate components that cooperate out of sight. The first of these is living microbes such as bacteria and fungi, which decompose material. The second is recent detritus of roots and organisms not long dead. The third consists of stable forms of humus which have resulted in dark, resistant compounds that endure for years. In contradistinction to the leaves at the surface or the undead debris, true organic matter becomes incorporated in the soil mass.

Carbon constitutes around 58 percent of soil organic matter by weight. This specific composition is the chemical fingerprint that distinguishes it from other materials. You can test soil samples for the existence of this carbon fingerprint. Laboratories employ combustion analysis to accurately measure the organic matter content.

The microscopic organisms known as microbial biomass are the hidden driving force behind soil fertility. These organisms process nutrients and create soil structure through their activities. I have seen fields double their productivity when microbial species thrive, and so many farmers underestimate this invisible workforce.

Stable humus develops slowly over time through biological processes. It does not decompose so readily as do fresh plant residues. It occurs in the form of dark, crumbly soil, which has an excellent capacity for retaining moisture. Its complex physical and chemical composition is an assurance of continued fertility on the farm and in the garden.

Chemical Makeup

- Carbon constitutes 58% of typical soil organic matter composition

- Essential nutrients include nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur minerals

- Micronutrients like iron and zinc bind within organic complexes

- Hydrogen and oxygen form structural components of organic molecules

Excluded Materials

- Undecayed surface plant litter remains separate from SOM classification

- Fresh animal droppings require decomposition before integration

- Synthetic fertilizers lack organic structure despite nutrient content

- Charcoal fragments exist independently until microbial colonization

Formation Timeline

- Fresh residues transform into stable humus over 1-10 years depending on climate

- Microbial processing dominates initial decomposition phases within weeks

- Mineral association stabilizes organic fragments within months to years

- Earthworm activity accelerates aggregation and humification processes seasonally

Global Variations

- Forest soils store 50-200 tons of carbon per hectare in organic layers

- Grassland soils develop deeper organic matter profiles than croplands

- Arctic peatlands preserve ancient organic matter due to freezing

- Desert soils contain less than 1% organic matter without irrigation inputs

Measurement Standards

- Loss-on-ignition: heating samples to 400°C (752°F) measures mass loss

- Walkley-Black method: chemical oxidation with potassium dichromate

- Modern spectroscopy analyzes carbon content via infrared reflectance

- Density fractionation separates particulate and mineral-associated fractions

Microbial Colonies

- Bacterial clusters appear as slimy films coating soil particles under magnification

- Fungal hyphae form white thread-like networks through soil aggregates

- Actinomycetes colonies create earthy aromas and grayish mats in decaying matter

- Protozoa regulate bacterial populations through continuous predatory feeding cycles

- Microbial biofilms protect colonies from environmental stresses like drought

- Enzyme secretions break down complex polymers into absorbable nutrients

Plant Detritus

- Fresh leaves show visible cellular structures during initial decomposition

- Twig fragments persist for months with identifiable bark patterns

- Root hairs decompose fastest while woody sections endure years

- Seed coatings contain protective compounds that slow microbial access

- Flower petals provide quick-release nutrients as they disintegrate

- Needle litter from conifers acidifies soil during gradual breakdown

Humus Complex

- Well-decomposed humus forms dark crumbly aggregates without plant structures

- Clay-humus complexes appear as shiny coatings on mineral surfaces

- Humic acids dissolve in alkaline solutions forming brown liquids

- Fulvic acids yield yellow solutions across all pH conditions

- Humin remains insoluble even in strong chemical extractants

- Humus colloids expand when wet to increase water holding capacity

Charcoal Fragments

- Wood-derived charcoal displays porous cellular structures under magnification

- Black carbon particles persist for centuries without chemical change

- Biochar amendments show visible black fragments throughout soil profile

- Charred grass residues form smaller particles than woody materials

- Ancient charcoal contributes to persistent carbon in terra preta soils

- Microbial colonization transforms inert charcoal into living habitat

Aggregate Formation

- Macroaggregates contain visible plant debris bound by fungal networks

- Microaggregates form dense clusters cemented by bacterial secretions

- Earthworm casts create distinctive granular structures in surface soil

- Root hairs physically bind particles into temporary aggregates

- Wet-dry cycles create visible cracks separating structural units

- Crumb structure indicates optimal organic matter decomposition balance

Formation and Decomposition

The first step in forming soil organic matter is the physical fragmentation of plant residues. This fragmentation of leaves, stems, and roots is done primarily by earthworms and insects. This shredding greatly increases the surface area of the plant material scraps, which are then colonized by microorganisms, initiating the process of conversion into organic matter. More than 90 per cent of the organic input comes from plant detritus.

Rates of decay vary widely with molecular structure. Simple sugars are gone in hours, while complex lignins exist for decades. Proteins are lost in days or weeks, while cellulose takes months or years. Temperature and moisture greatly accelerate or slow these natural processes.

Root exudates directly feed microbial communities through these associations. Plants exude sugars, organic acids, and enzymes, which stimulate beneficial bacteria and fungi. I have seen healthier crops when these partnerships are thriving underground. This can be stimulated by minimizing chemical disturbances.

Mineralization completes the cycle, transforming organic matter into nutrients that are available to the plant. Aerobic bacteria transform carbon into carbon dioxide and release nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur compounds. The natural fertilization production system feeds your plants without the use of synthetic inputs.

Mechanical Fragmentation

- Earthworms and arthropods physically break plant residues into smaller fragments

- Increased surface area exposes more material to microbial colonization

- Freeze-thaw cycles accelerate fragmentation in temperate climates

- Raindrop impact crushes delicate plant structures on soil surfaces

Microbial Colonization

- Bacteria establish biofilms on fresh organic matter within hours

- Fungal hyphae penetrate plant tissues using enzymatic excretions

- Actinomycetes target tougher cellulose compounds in later stages

- Microbial succession follows chemical availability shifts in residues

Biochemical Transformation

- Extracellular enzymes break complex polymers into soluble monomers

- Aerobic bacteria oxidize compounds releasing CO₂ and H₂O

- Anaerobic microbes produce methane and organic acids in waterlogged soils

- Nitrogen immobilization occurs when carbon-rich materials decompose

Mineralization Outputs

- Carbon converts to CO₂ (aerobic) or CH₄ (anaerobic) gases

- Proteins mineralize into plant-available ammonium and nitrate ions

- Sulfur compounds release sulfate through microbial oxidation

- Phosphorus liberates as orthophosphate ions at neutral pH

Humification

- Resistant compounds polymerize into complex humic substances

- Polyphenols and quinones react with amino acids forming stable complexes

- Clay minerals bind organic fragments through cation bridges

- Final products include fulvic acids, humic acids, and insoluble humin

Bacteria

- Aerobic species dominate well-drained soils consuming simple sugars

- Actinomycetes decompose chitin and cellulose in later stages

- Cyanobacteria fix atmospheric nitrogen in surface crusts

- Pseudomonads mineralize proteins releasing ammonium ions

- Anaerobic clostridia ferment compounds in waterlogged conditions

- Bacterial biomass doubles every 20 minutes under ideal conditions

Fungi

- Saprotrophic fungi secrete cellulases for plant cell wall decomposition

- Mycorrhizal species form symbiotic relationships with plant roots

- White rot fungi produce lignin peroxidase for wood breakdown

- Chytrids decompose pollen and keratin in wet environments

- Fungal networks transport nutrients across decomposition hotspots

- Hyphal strands can extend several meters through soil profiles

Earthworms

- Epigeic species process surface litter in organic-rich horizons

- Endogeic worms consume soil-organics mixtures belowground

- Anecic types pull surface residues into vertical burrows

- Castings contain 5x more nitrogen than surrounding soil

- Burrowing creates channels enhancing aeration and water flow

- Mucus secretions bind soil particles into stable aggregates

Arthropods

- Springtails fragment fresh litter with chewing mouthparts

- Mites regulate fungal populations through grazing activity

- Millipedes consume decaying wood increasing surface area

- Isopods process calcium-rich plant materials like bark

- Ants transport organic matter deep into nest chambers

- Beetle larvae tunnel through woody debris accelerating decay

Protozoa & Nematodes

- Amoebae consume bacteria releasing locked-up nitrogen

- Flagellates regulate bacterial populations in pore spaces

- Ciliates control fungal growth on organic surfaces

- Bacterial-feeding nematodes mineralize nutrients through excretion

- Fungal-feeding types puncture hyphae releasing cellular contents

- Predatory nematodes regulate populations of microbial grazers

Key Benefits and Functions

Soil organic matter significantly increases the soil's moisture-holding capacity. Humus holds twenty times its weight in moisture, while clay-humus complexes hold from fifteen to eighteen times. In agricultural regions, this results in a lesser necessity for irrigation, from thirty to fifty percent. The plants can survive longer periods between waterings during dry spells, thanks to the sponge-like nature of organic matter. Fields with high organic content require less frequent watering.

Aggregate formation varies greatly according to soil type. Sandy soils develop structure through the binding of particles by fungal networks. Clay soils will utilize polysaccharide glues secreted by bacteria. I have measured a 20% greater root penetration in aggregated soils. You can improve any soil type by regularly adding organic amendments.

Through cation exchange, nutrients bind to organic matter. Fixed potassium ions are associated with humus; magnesium binds to clay surfaces. This compensates for the leaching of nutrients that occurs during heavy rains. The plants obtain these minerals through the process of root activity. Organic matter acts as a slow-release fertilizer bank.

The storage of carbon has a direct influence on climate resilience. Each 1% increase in organic matter sequesters 8-10 tons of carbon per acre. This percentage offsets the carbon emissions from cars, equivalent to approximately 5,000 miles driven by you in your vehicle each year. Management of these choices contributes to larger solutions to environmental problems.

Soil Aggregation

- Fungal hyphae bind particles into water-stable microaggregates

- Polysaccharide glues from bacteria cement silt-clay complexes

- Earthworm casts form macroaggregates >2mm in diameter

- Root exudates create temporary aggregates around rhizosphere

Nutrient Cycling

- Cation exchange sites hold Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, K⁺ for plant uptake

- Mineralization releases 2-4 kg nitrogen per ton of organic matter

- Phosphorus binds in organo-metallic complexes preventing leaching

- Sulfur oxidizes to sulfate through microbial activity

Carbon Sequestration

- Mineral-associated carbon remains stable for decades

- Aggregate-protected carbon resists microbial decomposition

- Forest soils store 100-200 metric tons carbon per hectare

- Grassland soils sequester 0.5-1 ton carbon/acre/year

Erosion Control

- 1% organic matter reduces erosion by 20-33% on slopes

- Aggregate stability withstands 25 mm/hr rainfall impact

- Surface residues dissipate raindrop energy before soil contact

- Root networks anchor soil particles against water flow

Biodiversity Support

- 1 gram of soil contains up to 10 billion microbial cells

- Earthworm populations increase 3-5x in high-SOM soils

- Mycorrhizal networks connect multiple plant species

- Nematode diversity indicates balanced soil food webs

Stabilization Mechanisms

Organic matter bound to minerals attaches directly to clay through ligand exchange. Such covalent bonds can endure for decades. Organic matter that is aggregate-protected is mechanically entrapped within soil aggregates. These mechanisms represent different stabilization routes with varying persistence times.

There is substantial variation in the mechanisms and strengths of bonds. Stronger attachments from ligand replacement occur with organic compounds binding to the hydroxyls of minerals. Weaker attachments from Van der Waals forces arise from electromagnetic attraction. By the process of ligand exchange, clay soils seem better able to maintain C, which is mixed as a bonding material in clay.

Aggregate formation follows certain inevitable times: Macroaggregates form around fresh residues after a few weeks. Microaggregates accumulate inside them through a period of months or years. The earthworms hasten this process, producing water-stable structures. These natural times are directly influenced by your tillage practices.

Biochemical resistance is overrated. Molecular complexity can only provide temporary protection against decay. The physical and chemical methods are the primary means of long-term stabilization. The mineral composition of the soil is more of a determinant of the soil's ability to store carbon than the type of residue.

Mineral Interactions

- Clay minerals bind organic fragments through cation bridges

- Iron oxides form strong complexes with carboxyl groups

- Silt particles provide intermediate binding surface areas

- Allophane clays create nanoscale protective coatings

Aggregate Hierarchy

- Macroaggregates (>250μm) form around fresh residues

- Microaggregates (53-250μm) develop inside macroaggregates

- Silt-clay complexes stabilize within microaggregates

- Earthworm activity accelerates aggregate formation cycles

Chemical Bonding

- Ligand exchange creates covalent bonds on mineral surfaces

- Van der Waals forces adsorb proteins to phyllosilicates

- Hydrogen bonding stabilizes polysaccharide-mineral complexes

- Cation bridging connects organic acids to clay particles

Environmental Controls

- Freezing temperatures preserve ancient organic matter

- Waterlogging reduces oxygen availability for decomposition

- Alkaline pH enhances organo-mineral complex stability

- Drought conditions limit microbial decomposition activity

Microbial Influence

- Microbial necromass contributes to mineral-associated fraction

- Fungal melanins resist decomposition in dry conditions

- Biofilms create protective microenvironments for organic matter

- Enzyme inhibitors slow degradation of complex molecules

Managing Soil Organic Matter

Cover vegetation and reduced tillage promote distinct approaches to soil improvement. Leguminous covers, such as clover, fix nitrogen, whereas herbaceous covers build up biomass. Residue tillage preserves the soil's structure and shelters the soil's microbial inhabitants. Faster gains in nitrogen accumulation are achieved using cover crops, while better preservation of structure is obtained through minimum tillage. These systems can be effectively used together.

The best carbon-to-nitrogen ratios differ by type of amendment. Compost is best at a 20:1 ratio, with manure at a 15:1 ratio. The straw application requires a balancing act at a ratio of 80 to 1 with nitrogen sources. I adjust ratios based on soil tests to prevent nitrogen tie-up from starving plants.

Measurable organic matter increases follow consistent patterns. Annual compost applications boost levels 0.3-0.6% while cover crops deliver 0.1-0.3% gains. Reduced tillage adds 0.05-0.2% yearly. Your management intensity directly determines accumulation rates.

Proper timing, seasonally, is crucial for the amendment to be effective. Cover crops are planted 4-6 weeks before the first frost to allow for establishment before the onset of frost. Compost applications occur when the soil moisture level reaches 50% of the field capacity. Apply manure before planting to enhance nutrient availability. Timing will also avoid compaction on soils.

Residue Handling

- Burning crop residues destroys 90-100% of organic carbon

- Removing straw reduces annual SOM inputs by 1-2 tons/acre

- Solution: Chop and incorporate residues within 48 hours after harvest

- Alternative: Use no-till planting directly into residue cover

Tillage Practices

- Excessive tillage increases oxidation of soil carbon

- Each plowing pass reduces aggregate stability by 15-20%

- Solution: Adopt strip-till or no-till systems

- Alternative: Use subsoiling only when compaction exceeds 300 psi

Amendment Timing

- Incorporating organic matter in wet soil causes compaction

- Late-fall applications risk nutrient leaching before spring planting

- Solution: Apply amendments when soil moisture is at 50% field capacity

- Alternative: Time applications 4-6 weeks before planting

C:N Ratio Neglect

- High C:N materials (>30:1) cause temporary nitrogen deficiency

- Low C:N materials (<15:1) decompose too rapidly

- Solution: Balance amendments to 20-25:1 C:N ratio

- Alternative: Mix high-carbon straw with nitrogen-rich manure

Input Continuity

- Skipping annual inputs causes 0.5-1% SOM decline per year

- Solution: Maintain consistent organic matter additions

- Alternative: Establish perennial cover in alleys between crop rows

- Monitoring: Test SOM levels every 2-3 years to track changes

5 Common Myths

Organic matter in the soil is comprised mainly of visible plant material found on the surface.

While plant litter, or surface litter, is part of the organic input to the soil, true soil organic matter does not include undecomposed surface litter. True organic matter consists of decomposed products, microbial cells and stable humus formed from biological action in the soil for long periods of time.

Everyone knows that all humus is the same chemically whatever the source or origin.

The composition of humus is very different, fulvic acids being soluble in water and of low molecular weight, humic acids soluble in alkaline solutions, while humin is insoluble; these differ in permanence and function in normal environments and many mineral mixtures within special soil conditions.

Charcoal remains completely stable for thousands of years after burning.

Because of its aromatic structure charcoal is remarkably persistent, but it undergoes a slow surface transformation owing to microbial colonization as a result of oxidation and physical disintegration, which proceeds at decomposition rates depending upon climatic conditions and soil biology, at universally operating factors of a century or more, and which therefore is not a permanent stability.

Microbial activity generates the majority of soil organic matter in all environments.

Plant-derived inputs contribute approximately 50% of soil organic matter through root exudates and detritus, with microbial necromass proportions varying significantly across ecosystems from 30% in grasslands to 60% in forests depending on vegetation types and decomposition conditions.

Biochemical resistance alone determines long-term carbon storage persistence in soils.

Mineral-association mechanisms and physical occlusion within aggregates provide the primary stabilization pathways for carbon storage over decades, while biochemical recalcitrance only delays initial decomposition temporarily and becomes environmentally insignificant within months to years under typical field conditions according to soil science research.

Conclusion

Soil organic matter is the foundation of all terrestrial ecosystems. This living system supports forests, grasslands, and farmland worldwide. Your land management decision makes this essential foundation strong or weak. Healthy soils create resilient landscapes that meet environmental challenges.

The carbon sequestration potential of a specific field is affected by your management practices. Each 1% increase in organic matter sequesters an important amount of atmospheric carbon. The implementation of cover crops and compost applications turns a field into a carbon sink. This tangible impact helps combat climate change by using more sustainable agricultural practices.

Agricultural productivity is improved, and the health of the environment, as tracked by organic matter, is also enhanced. The higher the amount of organic matter, the greater the capacity for holding water becomes, and the less irrigation is required. The availability of nutrients facilitates crop production, but the use of chemical fertilizers is generally avoided. I have noted, for instance, that these methods yield 30% more produce than conventional methods.

Regenerative stewardship embodies the future of land management. It builds organic matter and creates food. Participating in this revolution fosters productive ecosystems for future generations. Every farm and garden contributes toward this betterment.

External Sources

Frequently Asked Questions

What actually constitutes soil organic matter?

Soil organic matter includes decomposed biological materials beyond surface litter, specifically:

- Microbial biomass like bacteria and fungi colonies

- Stable humus formed from fully broken-down organic polymers

- Root exudates released by living plants

- Charcoal fragments from incomplete combustion

Why is organic matter crucial for healthy soils?

Organic matter fundamentally transforms soil functionality through multiple mechanisms:

- Enables water retention up to 20 times its weight

- Creates habitat for beneficial microorganisms

- Binds nutrients in plant-available forms

- Forms stable aggregates preventing erosion

- Stores carbon long-term in mineral complexes

How does decomposition timing vary for different materials?

Decomposition rates depend entirely on molecular complexity:

- Simple sugars break down within hours or days

- Proteins require days to weeks for enzymatic cleavage

- Cellulose persists for months or years

- Lignin and charcoal resist breakdown for decades or longer

Can coffee grounds effectively improve soil quality?

Coffee grounds provide nitrogen benefits but require careful management. Their high nitrogen content aids plant growth, yet their acidity requires balancing with alkaline materials. Always compost grounds first to avoid nitrogen immobilization that could temporarily starve plants of nutrients during decomposition.

What defines truly organic soil?

Organic soil contains sufficient decomposed biological matter to sustain ecosystem functions without synthetic inputs. This requires measurable organic carbon levels supporting nutrient cycling, water retention, and microbial activity, distinct from soils dependent on chemical fertilizers for productivity.

Which management practices boost organic matter most effectively?

The most impactful regeneration strategies include:

- Cover cropping between growing seasons

- Applying composted organic amendments annually

- Reducing tillage depth and frequency

- Rotating deep-rooted and shallow-rooted crops

- Integrating livestock manure appropriately

Does organic certification guarantee optimal soil health?

Certification indicates avoidance of synthetics but doesn't automatically create healthy soils. Truly regenerative systems require active organic matter management through measurable practices like compost application and cover cropping, not merely substituting approved inputs for prohibited chemicals.

What are common misconceptions about humus?

Humus is frequently misunderstood as chemically uniform when it actually contains distinct fractions like water-soluble fulvic acids, alkali-soluble humic acids, and insoluble humin. Each fraction interacts differently with minerals and provides unique functional benefits in soil ecosystems.

How does organic matter combat climate change?

Soil organic matter serves as the largest terrestrial carbon sink through:

- Mineral-associated carbon storage lasting decades

- Aggregate-protected carbon sequestration

- Reduced decomposition rates in stable humus

- Long-term charcoal fragment preservation

Can soils become overloaded with organic matter?

Excessive organic matter causes nitrogen immobilization and compaction when improperly managed. Balance applications to maintain optimal carbon-nitrogen ratios and avoid waterlogged conditions that create anaerobic decomposition producing methane instead of stable humus compounds.