Exploring Leaf Vein Patterns in Nature

Written by

Olivia Mitchell

Reviewed by

Prof. Charles Hartman, Ph.D.The arrangement of leaf veins is important for differentiating plant groups: parallel (monocots) and netted (dicots).

Veins convey both water via xylem, and nutrients via networks of phloem tissue.

Netted venation is more resistant to tearing than parallel patterns in leaves.

Density of veins impacts the efficiency of photosynthesis and strategies for adaptations to the environment.

Venation patterns may assist in distinguishing edible plants from toxic resembling species.

Leaves that are mature may alter their vein networks in response to drought or shade stress.

Article Navigation

Observe closely any leaf and you will see beautiful leaf vein markings. These make up nature's great distributing system that conveys nourishing fluids through the plant. The vascular tissues function like concrete roads, conveying moisture from the roots and sugars resulting from photosynthesis. This system provides evidence of life and keeps plants alive and flourishing from day to day.

Three principal patterns of venation are found in plants. In some plants, the veins are straight like railway lines, as in grass. In some, the veins are netted, as in broad-leaved trees. In others, the veins are dichotomous, as in ancient plants, and are evenly divided as the prongs of a fork in old plants. Each pattern serves a distinct purpose in the struggle for existence.

Major Types of Leaf Venation

Monocots such as corn and lilies feature parallel venation, in which the veins run in straight lines directly from the base to the tip, without bending or branching. This simple arrangement works very well with the speedy vertical growth required in open fields. Dicots, such as oaks and maples, feature netted venation, in which the veins are interconnected into complex networks that spread over the surface of the broad leaves, distributing the products of nutrition.

Ancient species of plants, such as the ginkgo tree, exhibit a type of dichotomous venation, in which the veins separate evenly, resembling the branches of a fork in the road. This is a rare type of venation, producing a symmetrical branching habit not seen in modern plants. The leaves of the ginkgo are recognized by their fan-like shape and the veins radiating from the base, which separate several times.

Each of the venation types shows some advantage for the survival of the plants. Parallel veins help grasses conserve water in dry climates. Netted patterns give strength against wind damage in forest plants. Dichotomous branching enables the primitive plants to secure the maximum amount of light in exchange for the minimum amount of vein material.

Parallel Venation

- Structural pattern: Veins extend parallel from base to tip without intersecting across the entire leaf length

- Common plants: Monocots like wheat, rice, lilies, and most grass species exhibit this efficient linear pattern

- Functional advantage: Optimized water transport system supporting rapid growth in open-field environments

- Identification tip: Veins converge at leaf tips but never cross paths forming distinct parallel lines

- Ecological role: Dominates in wind-exposed habitats due to reduced tearing risk from flexible arrangement

- Subtype example: Some banana plants show minor lateral veins branching while maintaining parallel flow

Netted Venation

- Basic structure: Interconnected veins forming branching network patterns

- Plant examples: Dominant in dicots like oaks, roses, and tomato plants

- Subtypes: Pinnate (single midrib) in elms; palmate (radiating) in maples

- Functional advantage: Provides structural reinforcement for broad leaves

- Identification tip: Veins create visible polygons between intersections

- Evolutionary aspect: Allows complex leaf shapes in shaded environments

Dichotomous Venation

- Structural pattern: Symmetrical Y-shaped branching with equal divisions repeating at every junction

- Common plants: Ancient species like Ginkgo biloba and some ferns preserve this evolutionary pattern

- Functional advantage: Balanced load distribution provides exceptional wind resistance and flexibility

- Identification tip: No central midrib exists as all branches maintain equal thickness and importance

- Paleobotanical significance: Fossil records show this pattern dominated Permian-era (299-252 million years ago) ecosystems

- Conservation status: Considered living fossils with minimal evolutionary changes over 200 million years

Lateral Parallel Venation

- Structural pattern: Primary veins run parallel with smaller perpendicular veins connecting them laterally

- Common plants: Found in select palms like coconut and date palms showing grid-like reinforcement

- Functional advantage: Cross-connections provide structural reinforcement for large fan-shaped leaves

- Identification tip: Resembles ladder rungs between main veins creating rectangular cellular compartments

- Environmental adaptation: Withstands tropical storms through reinforced framework distributing impact forces

- Distribution note: Less common than standard parallel venation but crucial for large-leaved species

Pinnately Netted Venation

- Structural pattern: Single dominant midrib with smaller veins branching sideways like feather vanes

- Common plants: Deciduous trees including oaks, elms, and birches showcase this branching pattern

- Functional advantage: Hierarchical distribution supports broad leaves in shaded forest understories

- Identification tip: Secondary veins angle toward margins creating asymmetrical diamond-shaped areas

- Seasonal adaptation: Flexible network accommodates leaf expansion in spring and nutrient withdrawal in fall

- Water efficiency: Redundant pathways ensure continuous flow if individual veins get damaged

Palmately Netted Venation

- Structural pattern: Multiple dominant veins radiating from petiole attachment like outstretched fingers

- Common plants: Maples, sycamores, and ivy species display characteristic hand-like vein arrangements

- Functional advantage: Radial symmetry distributes mechanical stress evenly across leaf surfaces

- Identification tip: Primary veins meet at single point creating star-shaped junctions at leaf base

- Thermal regulation: Open network allows efficient heat dissipation during high-temperature conditions

- Evolutionary aspect: Enables development of lobed margins that increase photosynthetic surface area

Functions of Leaf Veins

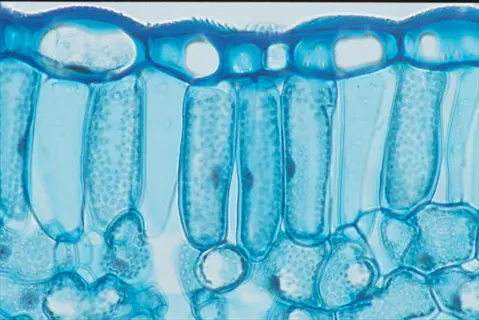

Leaf veins are essential vascular conduits with specialized structures. The xylem transports water and dissolved minerals from the base of the plant through the roots. In contrast, the phloem transports sugars produced by photosynthesis. This vascular highway system nourishes every cell in the leaves. It ensures that they receive the vital daily dose of nutrients needed for plant maintenance.

Lignin deposits apply mechanical reinforcement to veins that strengthen leaf structure. Thicker primary veins close to the midrib give support to leaf mass, while thinner branch veins give flexibility. This natural engineering provides tearing-preventing properties during storms, enabling plants to withstand wind and rain.

Vein density is a direct determinant of photosynthetic efficiency. Dense vein systems in sun plants reduce the distance that carbon dioxide must travel, increasing sugar production rates. In contrast, shade species exhibit more sparse patterns to conserve resources, showcasing one of nature's enduring efficiencies in diverse habitats.

Through the dynamics of fluids, they regulate temperature. The circulation of water in the xylem removes excess heat and protects delicate tissues. When subjected to heat stress, the flow rate of the vessels increases to prevent serious damage. This natural cooling system helps maintain the plant's proper functioning under changing conditions.

Hydraulic Transport System

- Xylem function: Specialized tubes move water and minerals from roots through Casparian strip filtration into leaves

- Daily volume capability: Mature trees transport over 100 gallons (378.5 liters) daily across extensive vein networks

- Structural composition: Hollow dead cells form continuous pipelines enabling efficient long-distance fluid movement

- Redundancy design: Branching vein patterns ensure continued function even when primary pathways suffer physical damage

- Environmental response: Flow rates automatically adjust based on humidity levels and available soil moisture content

- Visual stress indicator: Wilting occurs precisely when vein transport cannot match transpiration demand rates

Nutrient Distribution Network

- Phloem function: Sieve tube elements transport photosynthetic sugars to growing regions and storage organs

- Directional flexibility: Bidirectional flow moves sugars toward developing fruits or root systems as required

- Concentration mechanism: Sugar loading in veins creates osmotic pressure gradients driving flow through phloem

- Seasonal preparation: Autumn color changes signal nutrient withdrawal via veins before leaf detachment occurs

- Productivity correlation: High vein density (5-15 veins/mm²) enables 30% faster sugar transport in crops

- Biological parallel: Functions comparably to bloodstreams distributing nutrients throughout entire plant organisms

Structural Reinforcement Framework

- Lignin reinforcement: Veins contain rigid polymers providing steel-like reinforcement within leaf tissues

- Force distribution: Hierarchical branching dissipates impact energy from rainfall, wind gusts, or animal contact

- Thickness gradient: Primary veins near midrib measure 5x thicker than tertiary veins at leaf margins

- Engineering design: I-beam configurations optimize strength-to-weight ratios in species like Banksia marginata

- Damage containment: Interconnected networks prevent tear propagation beyond localized injury areas effectively

- Durability threshold: Leaves withstand forces up to 3 ounces (85 grams) per square inch before rupturing

Photosynthesis Support System

- Spatial optimization: Mesophyll cells cluster within 0.002 inches (0.05mm) of nearest minor vein pathways

- Gas regulation: Stomata along veins control carbon dioxide intake and oxygen release during daylight periods

- Density impact: High-density networks (8-20 veins/mm²) reduce CO2 diffusion distance by 40% in sun leaves

- Cellular alignment: Chloroplasts position along veins for direct sugar loading into phloem transport systems

- Efficiency correlation: Peak photosynthesis occurs when vein density matches stomatal distribution patterns

- Climate adaptation: Desert plants show lower vein density than tropical species with 50% higher averages

Thermal Regulation Mechanism

- Heat management: Vein fluids absorb excess thermal energy protecting photosensitive tissues from damage

- Convection process: Water circulation through xylem carries heat toward leaf margins for radiative cooling

- Density adaptation: Plants in hot climates develop 20% higher vein density than temperate zone species

- Crisis response: Emergency water flow activates when leaf temperatures exceed 104°F (40°C) thresholds

- Frost protection: Antifreeze proteins in vein sap prevent ice crystallization down to 14°F (-10°C)

- Thermal imaging: Infrared cameras reveal 5-7°F (3-4°C) temperature differentials along vein pathways

Venation in Monocots vs. Dicots

Grasses are monocots with parallel venation, their veins running up and down from the base to the tip, with no starting points or branches. This feature favors vertical growth under open conditions. Dicots, such as oaks, have netted venation, forming complex webs* which distribute the nutrients over the broad leaves very efficiently. The elements of venation are fundamentally of classification importance.

Water transport efficiency differs notably between groups. Monocot veins transport water more quickly in a longitudinal direction, which helps grasses survive drought. Dicot systems deliver water more homogenously via redundant routes. Therefore, leaves are larger. Each system evolved in response to environmental problems and demonstrates nature's adaptability.

Evolution shaped the types of venation, resulting in habitat advantages. Monocots have a parallel venation system, which helps conserve water in dry habitats, such as grasslands. Dicot systems have a more netted venation pattern, providing the added strength needed for survival in windy forest environments. All these different patterns have been developed over millions of years, optimizing the plants' chances for survival in the differing ecosystems.

Vein Pattern Architecture

- Monocots: Feature parallel venation where primary veins run longitudinally without branching intersections as seen in grasses like wheat and corn

- Dicots: Display reticulate venation forming interconnected networks with hierarchical branching patterns observed in broad-leaved plants such as oaks and roses

- Structural impact: Monocot veins maintain uniform spacing enabling linear growth while dicot veins create polygonal areoles supporting complex shapes

- Functional correlation: Parallel systems optimize unidirectional transport whereas netted systems provide redundant pathways enhancing resilience

Vascular Bundle Organization

- Monocots: Scattered vascular bundles without clear midrib differentiation in species like lilies and orchids allowing flexible bending

- Dicots: Organized vascular rings with distinct midrib and lateral vein hierarchy providing structural integrity in maples and tomatoes

- Developmental basis: Monocot bundles develop independently during growth phases while dicot bundles form coordinated systems early in development

- Strength implication: Scattered bundles provide omnidirectional flexibility against wind exposure in open habitats

Leaf Expansion Dynamics

- Monocots: Basal meristem growth allows continuous leaf elongation without vein distortion achieving vertical growth up to 1 inch (2.5cm) daily

- Dicots: Apical-dominant growth requires pre-patterned vein networks before expansion limiting maximum elongation rates significantly

- Growth limitation: Parallel venation restricts leaf width development compared to dicots which achieve greater surface area diversity

- Example contrast: Corn leaves maintain narrow profiles while oak leaves develop broad lobed structures

Water Transport Efficiency

- Monocots: Shorter radial distance from veins to cells (average 0.003 inches/0.08mm) enabling 15% faster longitudinal flow in grasses

- Dicots: Higher vein density (8-12 veins/mm² versus 5-8 in monocots) distributes water 30% more evenly across complex leaf surfaces

- Drought response: Monocot veins collapse faster under water deficit due to simpler structural organization in arid environments

- Performance data: Rice monocots achieve rapid hydration but maples maintain function during prolonged dry periods

Evolutionary Adaptations

- Monocots: Venation optimized for open habitats with high light availability emerging during Cretaceous (145-66 million years ago)

- Dicots: Networked veins support shaded environments through redundant pathways originating in Jurassic (201-145 million years ago)

- Climate specialization: Monocots dominate arid zones with water-efficient transport while dicots prevail in temperate forests

- Adaptive contrast: Wheat thrives in full sun through parallel veins whereas roses utilize netted veins for understory survival

How Venation Patterns Develop

In the embryonic stage of leaf development, the beginning of the formation of venation takes place, and the auxin hormones accumulate in the tips of leaves. This causes the initial formation of veins, a natural plan. The flow of auxin also forms a means of accomplishment, by means of which the vascular cells are differentiated and the primary system of veins is established, which determines the future growth habits.

Monocots and dicots follow different developmental schedules. Monocots, such as corn, develop parallel venation within 72 hours of germination, while in dicots, like beans, the midribs develop first, and the branch networks take days to form. This results from their special growth habits and structural requirements.

Changes in the environment shape the adaptive variations in vein density. For example, plants growing in bright sunlight have veins that are 20% denser than those of plants growing in shaded areas. Drought conditions lead to increased vein production within a few days, thereby improving the distribution of the water supply. These alterations occur without the growth of new leaves and are affected by internal changes in cells.

Embryonic Patterning Phase

- Initiation trigger: Auxin hormone accumulation at leaf primordia tip creates the first vein signaling point for vascular development

- Monocot pattern: Parallel veins establish simultaneously along the entire leaf axis within 72 hours of sprouting in grasses like maize

- Dicot pattern: Midrib differentiation precedes lateral branching over a 5-7 day period in broad-leaved plants such as oak trees

- Genetic control: Regulatory genes establish initial vein positioning through cellular differentiation signals in early growth

Primary Vein Formation

- Midrib development: Xylem cells differentiate progressively from leaf tip toward stem connection forming central support structure

- Monocot specialization: Single prominent midvein forms in cereal crops while minor veins develop strictly parallel configurations

- Dicot specialization: Thick midrib emerges with visible vascular tissue that can be observed during early leaf expansion stages

- Timeline completion: Primary vein network fully forms within 4 days post-emergence in fast-growing species like bean plants

Secondary Branching Stage

- Branching mechanism: Hormonal canalization creates flow paths determining vein angles typically between 45-60° (0.8-1.0 radian)

- Monocot limitation: Minimal secondary branching results in strictly parallel configuration with rare cross-connections in palms

- Dicot complexity: Hierarchical networks form with adaptive branching patterns responsive to light exposure and nutrient availability

- Environmental influence: Moderate light intensity increases vein density by 20% compared to low-light conditions in forest species

Tertiary Vein Development

- Mesh formation: Areoles complete when tertiary veins connect secondary branches creating functional photosynthetic compartments

- Density regulation: Cellular signaling mechanisms determine optimal vein spacing for efficient resource distribution patterns

- Functional maturity: Photosynthetic capability initiates when approximately 80% of the vein network becomes interconnected

- Climate adaptation: Plants in warm conditions (85-95°F/29-35°C) develop denser veins than those in cooler environments

Maturation and Specialization

- Lignification process: Secondary cell wall thickening completes over a two-week period providing structural rigidity to veins

- Stress responses: Drought conditions induce 15% higher vein density through hormonal signaling pathways in resilient species

- Evolutionary patterns: Ancient species like Ginkgo preserve dichotomous branching unchanged through geological time periods

- Final adjustments: Minor veinlets continue developing until the leaf reaches full expansion and functional maturity status

Venation Patterns in Plant Identification

Utilize the vein patterns of the leaves in the field for practical identification purposes. Rub the leaves backwards to feel the difference in the texture of the veins on the underside of the leaves themselves. Hold the leaves up to the light to see the concealed pattern of branching. These simple methods will serve well in separating similar-looking plants during nature walks.

Compare diagnostic venation features in species lookalikes. Maples have palmately netted veins spreading outward from a central point, while sycamores have triangular areoles. Raspberries present a vascular pattern where the venation itself seems flat with the surface. At the same time, poison ivy shows a venation where the veins themselves are lifted into ridges. These characters keep dangerous confusion from occurring.

Identify poisonous species using clues from leaf venation. Poison hemlock leaves show unequal branching of the veins. They are purple in color, whereas wild edible carrots exhibit no purple coloration. Bleeding yew trees have a venation of parallel veins, which is edible, but they have no scent when crushed. Take care to verify with other points of identification.

To accommodate identification for seasonal variations, vein structures in autumn become marked, so that the veins print showing the leaf scars become visible for identification in the winter. Spring budding shows repeating patterns from the embryo in the unfurling fiddle-heads. These seasonal modifications reflect the year-round garnering of knowledge and reference, so useful to psychologists and botanists.

Maple versus Sycamore Distinction

- Maple identification: Palmately netted veins with 3-5 dominant veins radiating from single petiole attachment point

- Sycamore identification: Truncated palmate pattern with secondary veins connecting to adjacent primaries forming triangular areoles

- Seasonal tip: Maple veins turn bright red in fall while sycamore veins remain green longer

- Safety note: Both species safe; confusing with toxic horse chestnut avoided by checking bud arrangement

Edible versus Toxic Berry Plants

- Raspberry (edible): Pinnate venation with serrated margins and curved secondary veins meeting at 60° angles

- Poison ivy (toxic): Alternate pinnate pattern with asymmetrical vein angles and no terminal veinlet

- Diagnostic feature: Raspberry veins flush with leaf surface; poison ivy veins create visible ridge texture

- Critical safety: Always wear gloves when handling potential toxic plants like poison hemlock which resembles wild carrot

Grass Family Differentiation

- Bamboo identification: Parallel veins with distinct cross-veins creating rectangular segments every 0.4-0.8 inches (1-2cm)

- Wheat identification: Strictly parallel veins lacking cross-connections with uniform 0.1 inch (2.5mm) spacing

- Field technique: Rubbing leaf backward reveals vein texture; bamboo feels ribbed, wheat smooth

- Ecological clue: Bamboo veins more prominent in shade-adapted leaves compared to sun-grown specimens

Oak Species Identification

- White oak: Rounded lobes with veins extending to sinus points without bristle tips

- Red oak: Pointed lobes with vein endings forming bristle tips at each marginal projection

- Magnification tip: 10x lens reveals red oak veins contain reddish tannins absent in white oak

- Winter ID: Persistent leaf bases show vein scars - red oak has V-shaped, white oak U-shaped

Medicinal Herb Verification

- Mint family: Reticulate veins with square stems and aromatic scent when veins ruptured

- Lookalike caution: Non-aromatic nettle has stinging hairs concentrated along major veins

- Harvest indicator: Optimal medicinal compounds when tertiary veins visible but not lignified

- Drying test: Veins retain green color longer than lamina in authentic medicinal specimens

Fern Identification

- Pattern characteristic: Dichotomous venation with equal Y-shaped branching at each vein junction

- Fiddlehead stage: Tightly coiled new leaves show embryonic vein patterns before unfurling

- Species example: Maidenhair fern displays delicate symmetrical vein patterns on fan-shaped fronds

- Habitat clue: Most ferns show prominent veins even in low-light forest understory conditions

Conifer Identification

- Needle structure: Single central vein running length of needle in pines versus multi-veined spruce needles

- Winter identification: Vein patterns remain visible on evergreen needles during cold months

- Resin clue: Broken veins release distinctive pine scent in conifers like fir and cedar species

- Toxic warning: Yew needles have parallel veins but contain deadly taxine alkaloids - avoid handling

5 Common Myths

All leaves which have parallel veins belong to the family of grasses and are safe to handle.

This is a mistake, for there are poisonous plants like the daffodil (Narcissus) and different species of the Iris family, which show veins that are arranged parallel, while grasses, as Johnson grass, contain compounds that form poisonous substances that cause prussic acid. The presence of parallel veins is only characteristic of the monocotyle devoted classification of plants, and not a safe family to which to belong. To some parallel-veined plants contact with the skin or mucous membrane might do serious damage, or if ingested may prove fatal. Identification should always be obtained before the practice of handling plants that are unfamiliar is indulged in.

Thicker veins indicates healthier plants with better nutrient transfer.

They have been related to structural support rather than nutrient efficiency. Most healthy desert plants like cacti tend to develop thinner veins for conservation. The more wind-resistant plants have flexible veins. Optimum plants have veins that are the right thickness for the density of the nutrients. If the veins are too thick, the plants may have a less-exposed leaf area for photosynthesis in some environments, even though their nutrient flow is better.

Leaves with netted veins are weaker and more easily torn than those with parallel veins.

The reticular netted venation gives much greater resistance to tearing by virtue of its machinery for the equal distribution of stress over various lines of resistance. Field observations show that netted venation is less easily affected by weathering than is parallel venation in the broad-leaved forms which are in question. This is because broad-leaved plants can better stand heavy rain and wind because of the redundant systems for the distribution of strain and shock. Besides this certain localities may be found where the main tear is not carried on beyond the area of framework supporting it.

Vein patterns don't give any indication of the edibility or nutritional value of the food.

Venation affects the distribution of the nutrition, as well as the concentration of the toxins. Poison hemlock has irregular branching with the associated purple discoloration of the veins, whereas edible wild carrots have none. Heavy venation in the spinach allows it to transport the food faster, while the various nightshade types have concentrated the alkaloids in certain vascular systems. Always check the symmetry of the veins and the color before partaking of any thing which is gathered.

Once the leaf has developed fully, plants cannot change their vein patterns.

Mature leaves visibly remodel their leaf venation gum during stress. For instance, under drought stress tomato plants put on denser tertiary veins in a few days to help the distribution of water in the leaf, while shaded leaves will expand the existing networks through an area as large as 20% to capture more light. In these cases, the change is observed without the formation of new leaf tissue by their altered cell activity along the veins.

Conclusion

Leaf vein patterns are the vital transport systems of nature that distribute water and nutrients to all parts of every plant. This elaborate system is a road system, and its arterial nature is life, giving vitality to plants. Understanding these patterns offers insight into how nature effectively addresses complex distribution problems in diverse environments.

Utilizing your vein knowledge to create sustainable gardens. Plants that have the proper venation for your climate use less water and require less care. When plants are grouped according to their type of venation, a balanced ecosystem is created. Less maintenance is needed for healthy gardens from year to year, as long as the pollinators are allowed to thrive.

Identifying veins helps forage safely and plant. Knowing vein design helps eliminate rough, edible plants that resemble poisonous ones. Note the vein texture, symmetry, and colour of the plants before gathering them. Knowing this is your safeguard and helps with knowledge about plants you can find in the wild with confidence.

Explore the plants around you for the revelation of these wonders of nature. Next time you get a leaf, hold it up to the light, and follow the lines that are seen in it. Do you notice any peculiarities of markings that differ between the leaves of different plants? This simple observation will lead to a greater appreciation of the wonderful complexities that exist in the realm of plant life at your very doorstep.

External Sources

Frequently Asked Questions

What are leaf vein patterns?

Leaf vein patterns are the structural arrangements of vascular tissues that transport water, nutrients, and sugars throughout plant leaves. These patterns include parallel veins in grasses, netted veins in broadleaf plants, and dichotomous branching in ancient species like ginkgo.

How do leaf veins function?

Leaf veins serve multiple essential functions:

- Xylem tissues transport water and minerals from roots

- Phloem distributes sugars produced during photosynthesis

- Provide structural support against wind and weather damage

- Regulate temperature through fluid circulation systems

What are the main venation types?

The three primary venation patterns found in nature include:

- Parallel venation: Straight veins running lengthwise in monocots

- Netted venation: Branching networks forming meshes in dicots

- Dichotomous venation: Symmetrical Y-shaped branching in ancient plants

Can venation identify plant types?

Yes, venation patterns are reliable identification tools. Monocots display parallel veins while dicots show netted patterns. Specific arrangements like palmate veins distinguish maples, and pinnate veins identify oaks. Venation also helps differentiate edible plants from toxic lookalikes.

Do veins indicate plant health?

Venation provides visible health indicators:

- Discolored veins may signal nutrient deficiencies

- Collapsed veins indicate dehydration stress

- Abnormal thickening suggests disease or pest damage

- Asymmetric patterns reveal genetic mutations or environmental stress

How do monocot and dicot veins differ?

Key differences include:

- Monocots: Parallel veins with scattered vascular bundles

- Dicots: Netted veins with organized vascular rings

- Monocots grow continuously without vein distortion

- Dicots require pre-formed vein networks before expansion

Can veins change after leaf formation?

Mature leaves adapt their vein networks in response to environmental conditions. During drought, plants develop denser tertiary veins for better water distribution. Shaded leaves expand existing networks to capture more light through modified cellular activity along vascular pathways.

What venation misconceptions exist?

Common myths include:

- Parallel veins always indicate safe plants (false: some are toxic)

- Thicker veins mean healthier plants (false: desert plants have thin veins)

- Netted veins are weaker (false: they resist tearing better)

- Venation doesn't affect edibility (false: toxins concentrate in veins)

How does venation affect photosynthesis?

Vein density directly influences photosynthetic efficiency. High-density networks reduce diffusion distance for carbon dioxide while optimizing sugar transport. Plants in sunny areas develop denser veins than shade species, with optimal vein-stomata alignment maximizing light conversion.

Why study leaf vein patterns?

Understanding venation helps with:

- Accurate plant identification for foraging safety

- Diagnosing plant health issues through vein analysis

- Developing drought-resistant crops via vein adaptation

- Preserving biodiversity through evolutionary pattern studies